Those who have been to Salt Lake City have probably viewed, or even floated in, Great Salt Lake. The lake is about 1/5th the size of Lake Ontario and is very salty. There are no out flowing rivers, and evaporation has decreased the average water level. Until a change occurs to bring a wetter climate, the lake will continue to shrink.

Now if you’d been here 17,000 years ago you would have seen a lake as big as Lake Superior, which flowed north through Zenda, Idaho, where for many years it ran over a dam of gravel. When the gravel soil dam eroded suddenly, the lake poured out in a tremendous flood. Over time the river cut back upstream to Red Rock Gap where the flow of water slowed while it eroded the limestone rock of the gap.

![Massacre Rocks Park 19-14 [800x600]](http://blog.stonesstravelguides.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/19-14-800x600-300x191.jpg)

The flood was one of the greatest floods of the continent. Water equal to the contents of Lake Ontario was suddenly let loose and with a crest over 100 metres, it surged down the narrow valley with three times the flow of the Amazon River. It probably took only a few weeks to drop the lake level 100 metres or more.

The rush of the water scrubbed the cliffs bare of soil. It peeled the black basalt rock off the cliff sides and from the bottom of the waterway. These huge blocks of rock tumbled and crashed into each other creating small pieces which became smoother and rounder the farther they rolled.

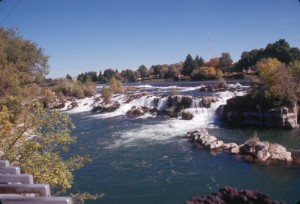

Where the route was narrow, the water with its load of sand and rocks, cut it deeper and created great waterfalls that plunged over the cliffs and bored massive plunge pools at their bases.

Where the valley was wide the water spread out and slowed leaving sand settling into great ripples, similar to the ripples at the beach, only 50 metres or higher. Many of the rounded rocks were left to litter the valley bottoms and they so much resembled a field of melons that one place is called Melon Valley.

The flood turned some areas into scablands, but it did leave some attractive legacies. Twin Falls drops 55 metres and just downstream the beautiful cascading Shoshone Falls, falling 64 metres. The only problem is the destruction of the waterfalls by taking away the water to create electrical power production and for irrigation. Try to see them in their glory on a wet spring when the water is really moving.

At Massacre Rocks St. Park you will see large hunks of basalt moved here by the massive surge of water. Down stream at The Twin Falls City, the Perrine Bridge vaults across the Snake River Canyon. There is a viewing platform at the ends of the bridge. It’s a good place to visualize the frothing water removing dark colour basalt from the cliffs and also deepening the gorge. There used to be springs from the cliff bottom, but that was before they started irrigating 300,000 acres of desert to create farms.

West of Twin Falls is the Hagerman Valley, and Thousand Springs, where it is often

possible to see hundreds of small springs bursting from the cliff walls and making small waterfalls into the canyon. What is perhaps interesting about these springs is that their water has flowed 250 kilometres under a thick layer of lava. This water is supposed to be the water from the Big Lost River and the Little Lost River which vanished under the lava on the north side of the Snake River Plain. Again, in the summer, irrigation may have caused the springs to dry up.

Bruneau Dunes State Park has small lakes backdropped by dunes up to 140 metres high. It is thought that much of the sand to create these dunes came during the flood.

To read more about these areas see ‘The Lure of Pine and Sage’ one of the Touring North America scenic guide books. Visit www.stonesstravelguides.com